Flint Knapping [2]

Posted by Davine Sutherland - 16:24 on 25 January 2018

I came to this session with little idea of the subject, and left with more knowledge than I could have expected, a lively sense of flint’s key role in prehistoric life, and a basic practical understanding of how it is worked, gained from demonstration and hands-on experimentation. This session with flint-knapper James Dilley, from the University of Southampton, was unexpectedly fascinating and rewarding.

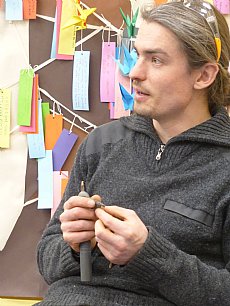

The floor was covered with a huge tarpaulin, still with flint nodes and flakes from the morning session, and James on a chair amidst them. There was also a ring of chairs inside its edge for the active participants. The session began informally, with us watching James working on a barbed flint arrow-head, a process involving constant pecking away with a copper-pointed hand-tool, with each peck needing body-pressure, not just the hand, for power and precision. Just watching this rhythmic yet careful process on the tiny artefact sucked in the participants with no need for an introduction, and James talked us through what he was doing, and why. This set the tone for the whole session, with comment, explanation, and demonstration flowing naturally, and allowing for spontaneous questions. James has a calm, warm, practical manner, and dry humour – and has got ‘show and tell’ down to a fine art.

The floor was covered with a huge tarpaulin, still with flint nodes and flakes from the morning session, and James on a chair amidst them. There was also a ring of chairs inside its edge for the active participants. The session began informally, with us watching James working on a barbed flint arrow-head, a process involving constant pecking away with a copper-pointed hand-tool, with each peck needing body-pressure, not just the hand, for power and precision. Just watching this rhythmic yet careful process on the tiny artefact sucked in the participants with no need for an introduction, and James talked us through what he was doing, and why. This set the tone for the whole session, with comment, explanation, and demonstration flowing naturally, and allowing for spontaneous questions. James has a calm, warm, practical manner, and dry humour – and has got ‘show and tell’ down to a fine art.

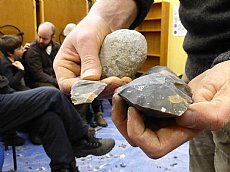

There followed basic information and techniques, always with demonstration – getting to know your material and its properties, the idea of shock waves, and how to make it all work for you. Starting with a node of flint, you try to find the best place to spit it into a couple of large ‘cores’ – typically a rounded bottom with a flat top, the ‘platform’, your starting point for systematically and rhythmically hammering off useful flakes of flint, the longer the better for knife-type implements. This is done with a ‘hammerstone’, a large beach pebble you can hold comfortably, and you strike down on the platform just inside the edge of the core, which you have to hold sloping downwards, your hand resting on your leg for support. If you strike on the edge itself, you’ll just damage the core and not get a clean flake. Skilled knappers can hammer off fine, even flakes round and round the core, like taking petals off a flower, with little or no waste. And James is skilled – he started at 10 years old almost because his dad told him not to, as it was too dangerous – flint flakes can be razor-sharp. The bug bit him and he became an expert even as a teenager. Flint is mainly found in the south of England, though tools from there made their way north, but there is also an area in Aberdeenshire where a caramel-coloured flint is found.

There followed basic information and techniques, always with demonstration – getting to know your material and its properties, the idea of shock waves, and how to make it all work for you. Starting with a node of flint, you try to find the best place to spit it into a couple of large ‘cores’ – typically a rounded bottom with a flat top, the ‘platform’, your starting point for systematically and rhythmically hammering off useful flakes of flint, the longer the better for knife-type implements. This is done with a ‘hammerstone’, a large beach pebble you can hold comfortably, and you strike down on the platform just inside the edge of the core, which you have to hold sloping downwards, your hand resting on your leg for support. If you strike on the edge itself, you’ll just damage the core and not get a clean flake. Skilled knappers can hammer off fine, even flakes round and round the core, like taking petals off a flower, with little or no waste. And James is skilled – he started at 10 years old almost because his dad told him not to, as it was too dangerous – flint flakes can be razor-sharp. The bug bit him and he became an expert even as a teenager. Flint is mainly found in the south of England, though tools from there made their way north, but there is also an area in Aberdeenshire where a caramel-coloured flint is found.

As well as sharp flakes, heavier-duty flint tools were also needed, such as axe and adze-heads. Further hammering techniques were shown and a usable axe-head emerged in front of our eyes. Smaller, rounded flakes also have their uses, such as scraping tools for leather-work – one of these also grew from a rough-looking thick flake, and the special characteristics needed – not too sharp, not too blunt, no abrasive edges etc, became clear as he went along. Even tiny sharp flakes can be worked on quickly to produce ‘microliths’, small tooth-like blades for the edges of fishing tools or non-barbed arrow-heads. Even toothed saws can be made with sharp flakes cutting into other sharp flakes. All the items he worked on were passed round for us to feel their weight, balance and different edges and planes, and will be retained by ARCH.

As well as sharp flakes, heavier-duty flint tools were also needed, such as axe and adze-heads. Further hammering techniques were shown and a usable axe-head emerged in front of our eyes. Smaller, rounded flakes also have their uses, such as scraping tools for leather-work – one of these also grew from a rough-looking thick flake, and the special characteristics needed – not too sharp, not too blunt, no abrasive edges etc, became clear as he went along. Even tiny sharp flakes can be worked on quickly to produce ‘microliths’, small tooth-like blades for the edges of fishing tools or non-barbed arrow-heads. Even toothed saws can be made with sharp flakes cutting into other sharp flakes. All the items he worked on were passed round for us to feel their weight, balance and different edges and planes, and will be retained by ARCH.

As well as copper-pointed pecking tools, hammerstones and other flints, antler times were also used as hammers, peckers and piercers for various types of work. James only uses tools that are known to have been used in prehistoric times – he has pioneered various experimental archaeological techniques himself, and discovered, for example, the best kind of adzes to make for creating dugout canoes – one of which he has of course also made, and sailed. He also works in bronze, and organic materials. A fascinating selection of his work was on display.

As well as copper-pointed pecking tools, hammerstones and other flints, antler times were also used as hammers, peckers and piercers for various types of work. James only uses tools that are known to have been used in prehistoric times – he has pioneered various experimental archaeological techniques himself, and discovered, for example, the best kind of adzes to make for creating dugout canoes – one of which he has of course also made, and sailed. He also works in bronze, and organic materials. A fascinating selection of his work was on display.

By now we were all very keen to get into the hands-on session, and that was great fun, and a real learning experience. Kitted out with goggles and gloves (flint chips are sharp), we were given cores and hammerstones, and shown how to hold them, and got on with trying to put the theory into practice. James moved around and gently redirected us, gave us reminders and tips, and encouraged us. Once you get into a rhythm, and strike off several usable flakes in a row, it becomes quite addictive, and very frustrating when that spell of success breaks. It’s also hard work, and you would need to take breaks to avoid repetitive strain injury. You can also only do it in a well-ventilated room (which we had), or outside, due to the sharp dust particles – in the old days, flint knappers working in poor conditions often died young of silicosis of the lung. Flint-knapping , we learned, is actually a trade that was still in demand into the 20th century, particularly for making the flints in old types of guns, and for hunting rifles even in recent times. In view of our own amateurish efforts, it was humbling to think of men with James’ skills stretching back through the ages.

I have to thank not only James himself, but ARCH for their vision in holding this series, and for them and their funding partners for enabling James with his vanful of heavy materials, displays and so on to drive up from Southampton for local workshops up here. I think our appreciation and interest was palpable.

You can read more about James’s varied work on his website and about flint knapping in more detail here

Top four pictures copyright Davine Sutherland; the bottom one (copyright ARCH) shows Davine (left) having a go.

The Experimental Archaeology: Learning about technologies in the past project has been funded by Historic Environment Scotland and the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Add your comment below

- Recent Blog Articles

- Learning Resources

- Crafting Day October 2018

- Medieval Coinage Workshop

- Viking Ring-Money workshop

- Thomas Telford Workshop

- Monthly Blog Archive

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017